High up on Donald Trump’s 2018 wishlist seems to be Afghanistan’s huge mineral wealth. But the president is walking into a minefield.

Without serious action to reduce the massive risk of conflict and corruption, his push for new contracts is likely to do much more for the Taliban than America.

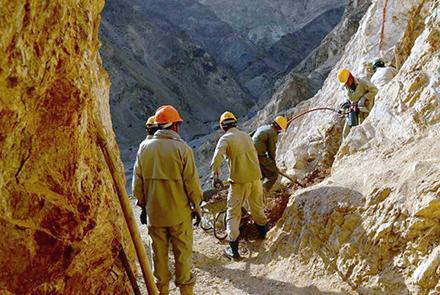

Afghanistan has massive mineral reserves, even if poor infrastructure makes them less valuable than the top-line numbers suggest. But those riches have done precious little to help the Afghan people, who have seen a fraction of the revenues that they should have — even as mining has been second only to narcotics in funding the Taliban.

Competition over mines among “pro-government” strongmen has turned parts of the country that staunchly resisted the Taliban — like Badakhshan province — into hotbeds of the insurgency. Locals angry at exploitation which does little to help them have backed the takeover of mines by illegal militias.

Meanwhile, major concessions like the Aynak copper mines have seen allegations of large-scale bribery, and both US and Afghan officials say the Ministry of Mines lacks the capacity to manage new contracts.

Any new mining project in Afghanistan is at very grave risk of falling foul of one or more of these dangers. The main threat to the sector is not a lack of investment, though that is certainly an issue: it is the lack of governance.

This is the environment in which America is pushing for new contracts. It is not clear exactly what is planned at this stage, and the desire to develop mining is not wrong in itself. But a few things are triggering alarm bells.

The first is the possibility that mines will be given cheaply to US companies, as compensation for America’s commitment in Afghanistan.

Erik Prince, founder of the deeply controversial Blackwater security company, has set out a vision of a “strategic mineral resource extraction funded effort” against the Taliban, according to a pitch obtained by BuzzFeedNews, echoing the colonial-era East India Company.

For Afghans, whose ancestors fought against imperialism just as Americans did, that is a recipe for outrage.

Of course, Prince does not represent the US government, even if he has close ties to it, and the Pentagon is reportedly opposed to Prince's suggestion.

But Trump has secured agreement from the Afghan president that US companies will “help … develop” Afghan resources. That implies something other than open allocation processes with the best bid winning.

The fear is an Afghan version of the idea that America should have “kept the oil” in Iraq. That would appropriate resources from one of the world’s poorest countries to benefit a few American companies, not even America in general, given the US would likely have to make up the resulting drop in Afghan revenue.

It would fit neatly into the Taliban narrative of America as an occupying force, extracting resources while leaving war in its wake. However unfair that narrative is, it is not hard to see how it will resonate. America is not here as a mercenary, but this would make it one.

The second is that contracts are being pursued without adequate regard to the risks. Two copper and gold deals currently on the table are particularly worrying. Currently a government minister, Sadat Naderi reportedly has a stake in the companies named as the preferred bidder for two of the contracts — a breach of Afghan law if the deal is finalized without this being addressed. The gold mine in the Badakhshan province, meanwhile, is largely in the hands of the Taliban.

Meanwhile, CENTAR, an investment company and key international partner in the project, has declined to publicly respond to our questions on these issues or comment on who will pay security costs, what benefits local communities will see, what guarantees there will be for transparency, and what happens if insecurity affects extraction.

Despite this, a “compact” of Afghan commitments negotiated with the US government includes both the resolution of the contracts and the launch of a new round of tenders in January 2018 — something which is bound to exert pressure on the Afghan government to close the deals.

This is the blind spot at the heart of American policy.

Realistic reforms like open bidding, automatic transparency mechanisms, security reforms, and giving communities a financial stake in legal mining are not silver bullets, but they could significantly reduce the scale of abuses.

Given the obvious risks, the US and Afghan governments should be urgently pushing these protections as a basic insurance policy, not just against the damage abuses would do, but against the biggest threats to the commercial success of the projects themselves.

Instead, while the Afghan government has made some very welcome commitments, little has yet been put into practice.

We want Afghan mining to flourish, and don’t take a knee-jerk position against any project. But at an absolute minimum, questions like those we raised need to be convincingly answered first, not just with bland assurances, but with concrete reforms and legal guarantees embedded in contracts and in the mining law.

And the Afghan government has to be ready to say no if a project is too risky, or could be done more profitably once conditions improve. Even if there is some argument for one or two “loss leaders” to show Afghanistan is open for business, they should not involve major assets.

If America wants to help develop Afghanistan’s resources in a way that avoids clear dangers, gets the best price possible, and builds institutional foundations for the future, they will be warmly welcomed. If they do otherwise, they risk disaster not just for Afghans but for their own interests, ironically while making even short-term commercial success less likely.

America is right to want Afghan mining to grow — but it needs to stop treating it as a quick fix, and start building for the long term.

Ikram Afzali is the executive director of Integrity Watch Afghanistan, an Afghan civil society organization fighting corruption and other abuses.

Stephen Carter is the Afghanistan campaign lead of Global Witness, an international civil society organization working to prevent conflict and corruption, especially around natural resources.